The previous chapter introduced the basic text formatting properties of CSS, but that was only one aspect of styling pages. Defining the layout of a web page is an entirely different beast. That’s what this chapter is about.

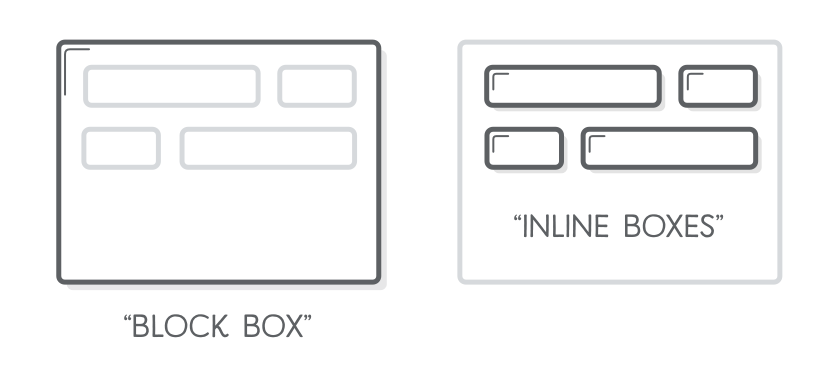

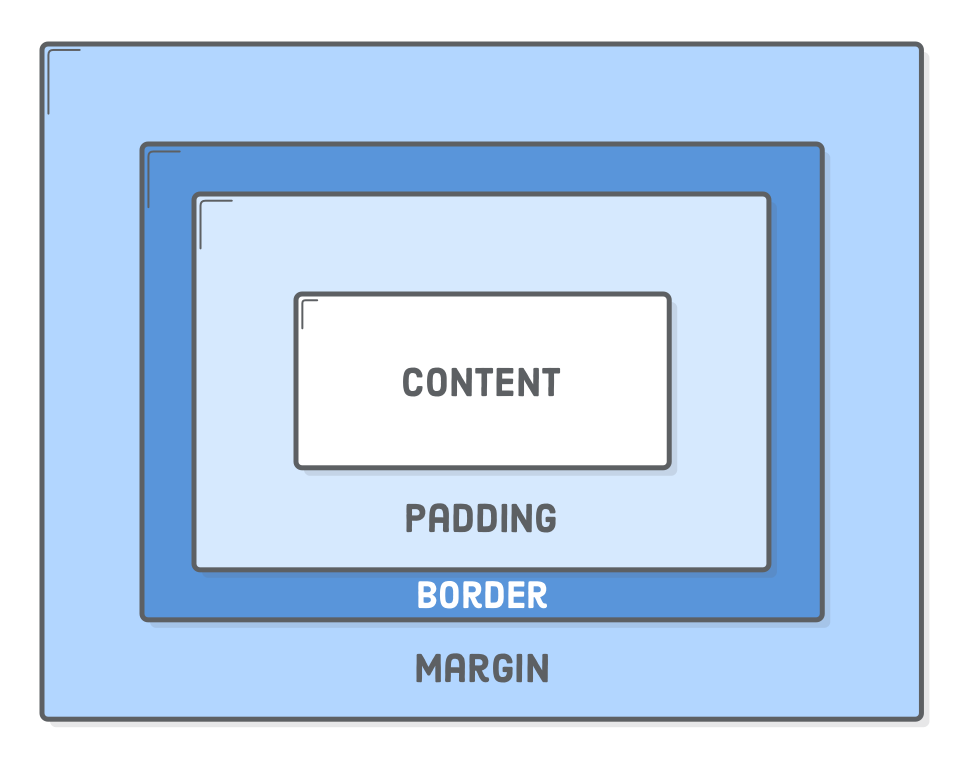

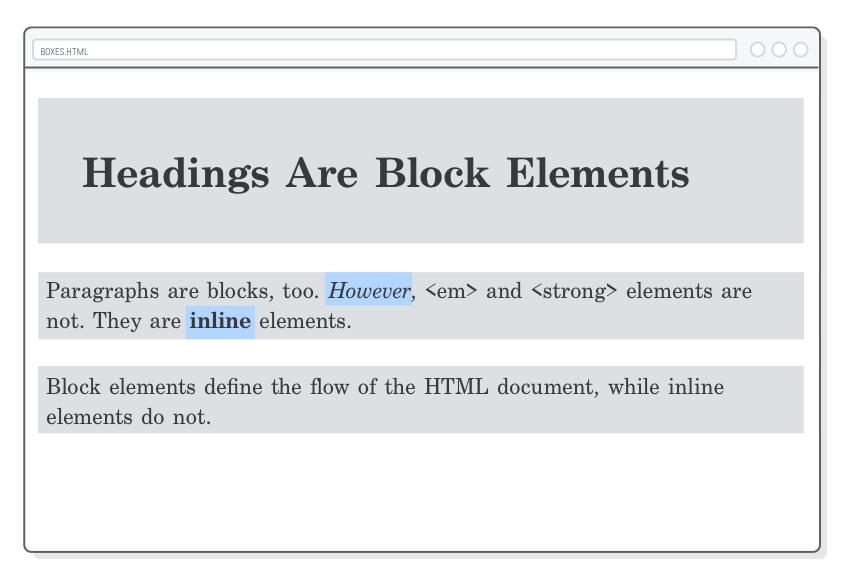

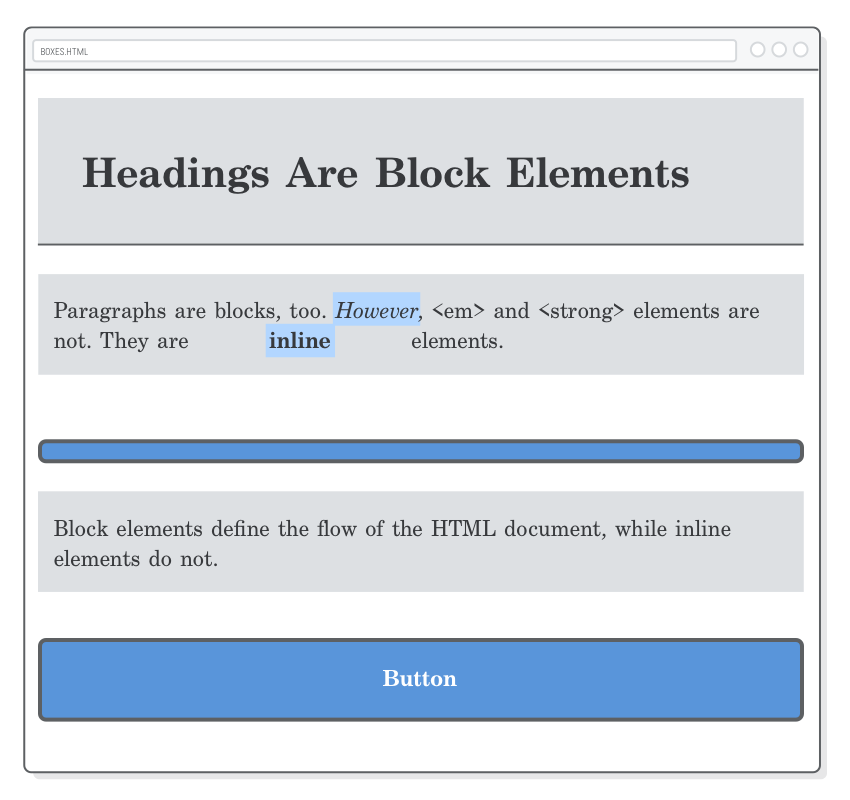

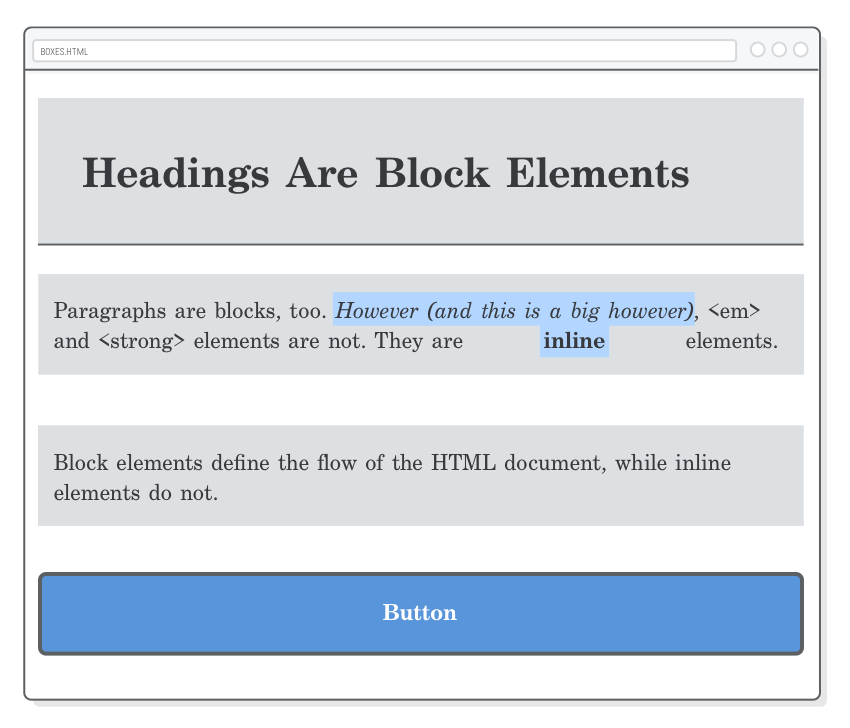

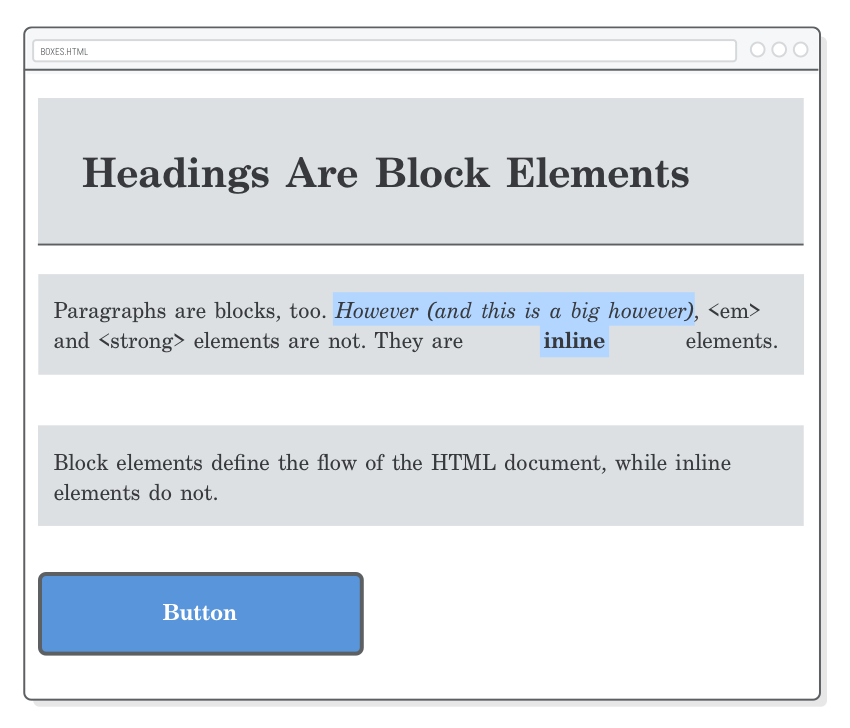

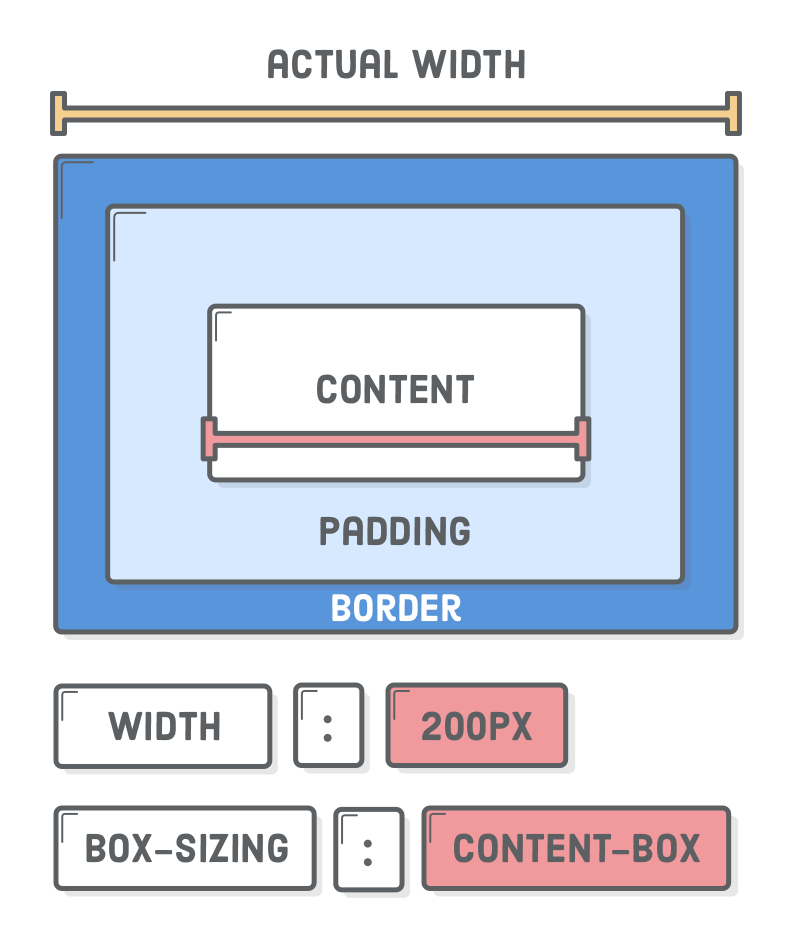

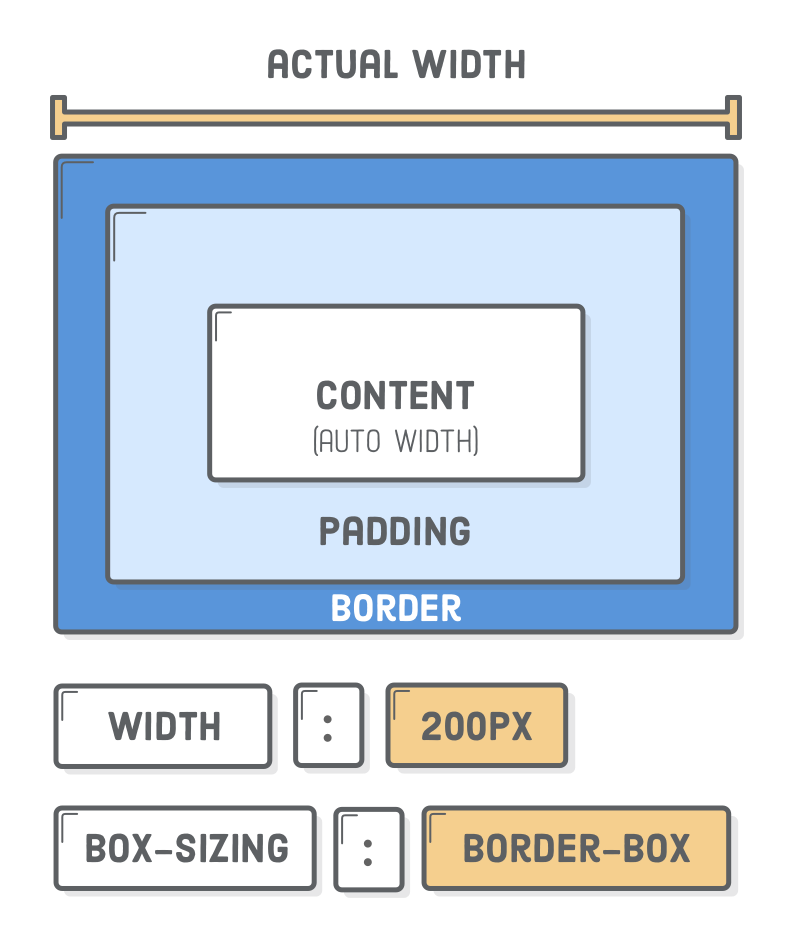

The “CSS box model“ is a set of rules that define how every web page on the Internet is rendered. CSS treats each element in your HTML document as a “box” with a bunch of different properties that determine where it appears on the page. So far, all of our web pages have just been a bunch of elements rendered one after another. The box model is our toolkit for customizing this default layout scheme.

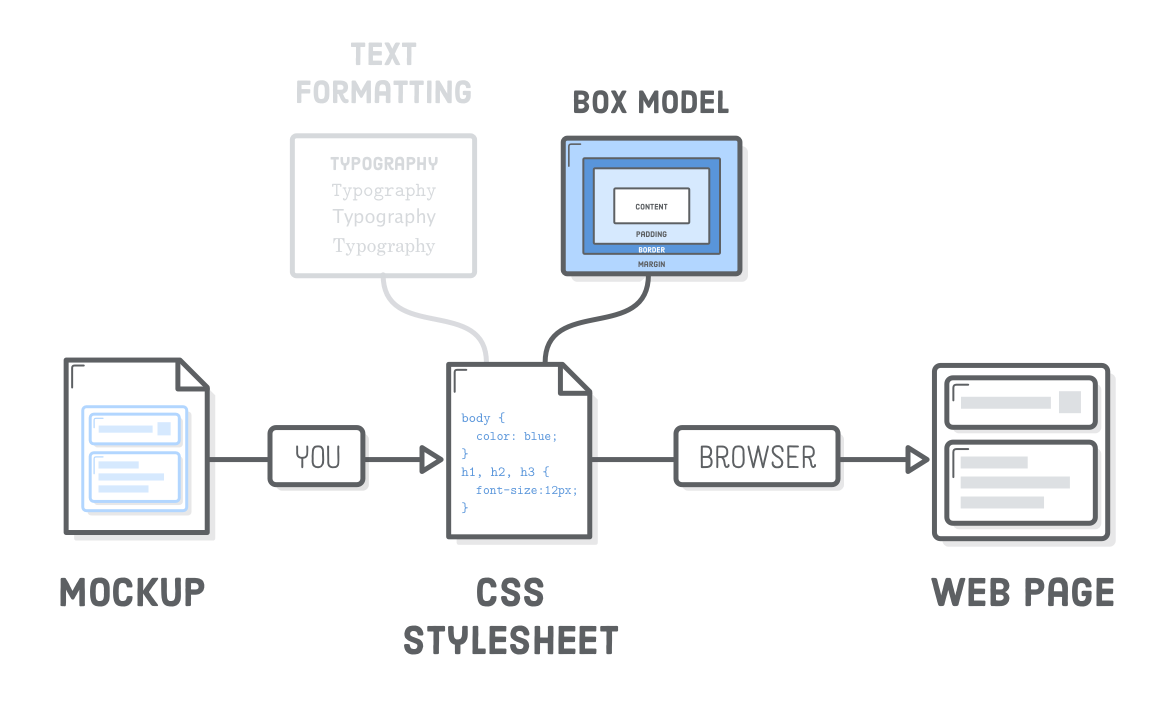

A big part of your job as a web developer will be to apply rules from the CSS box model to turn a design mockup into a web page. As you work through this chapter, you might find yourself wondering why we have to learn all these rules instead of just uploading a giant static image of a web page (i.e., a mockup) to a web server and calling it a day.

Indeed, this would make life a lot easier; however, if we didn’t separate out our content into HTML, search engines would have no way to infer the structure of our web pages, we couldn’t make our site responsive, and there would be no way to add fancy animations or interactivity with JavaScript. That’s a big enough trade-off to make CSS a worthwhile cause.

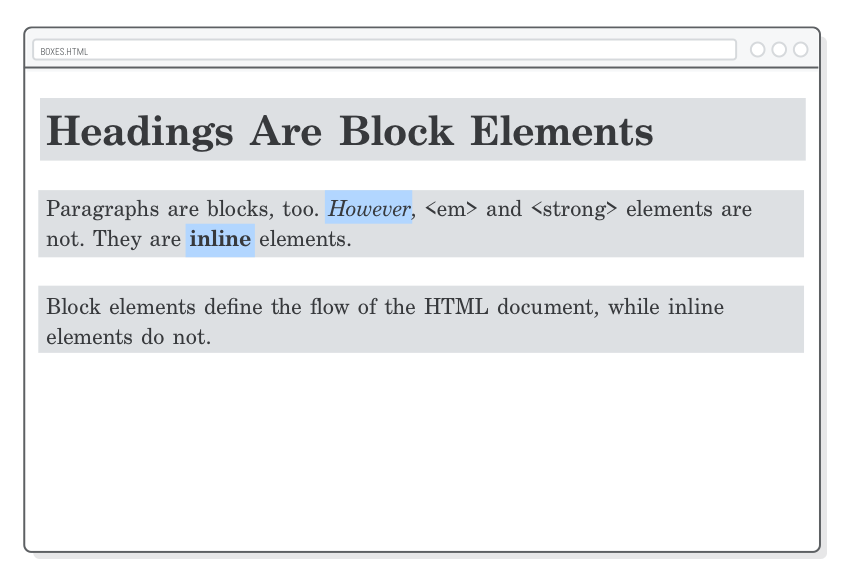

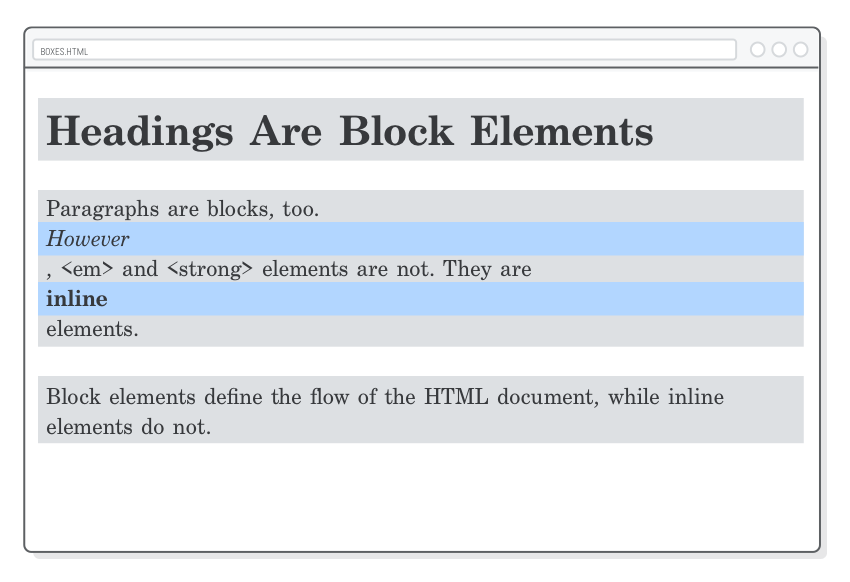

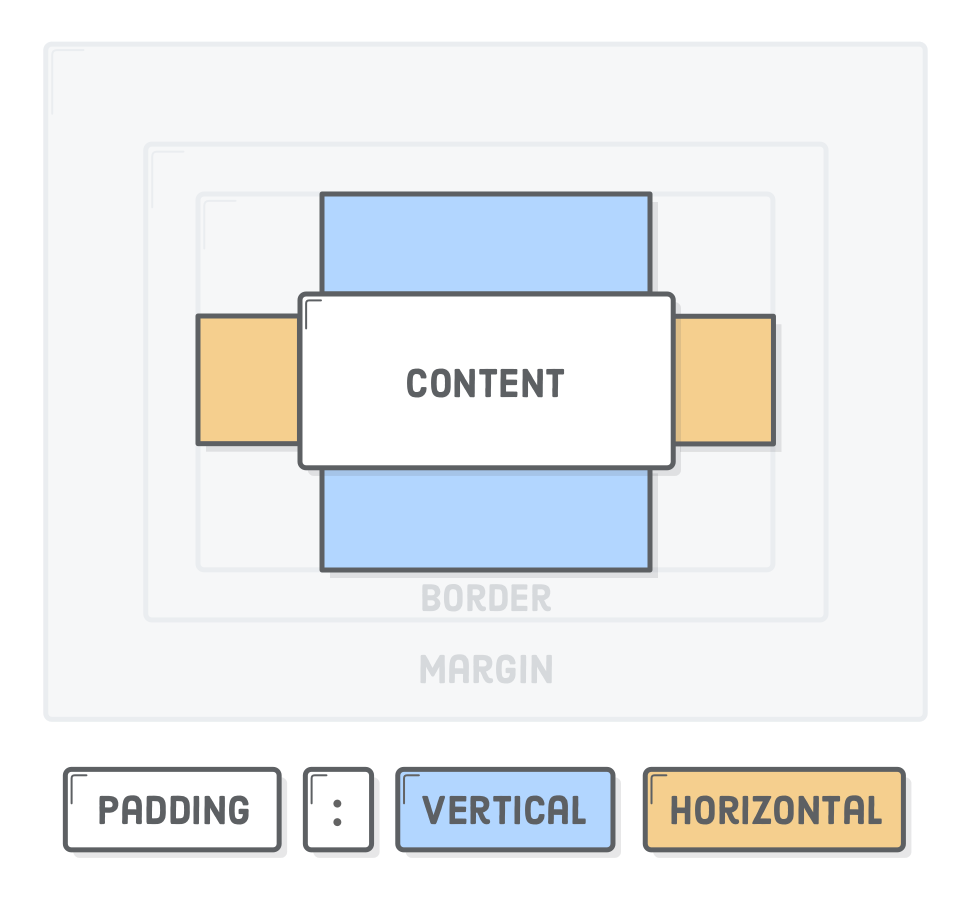

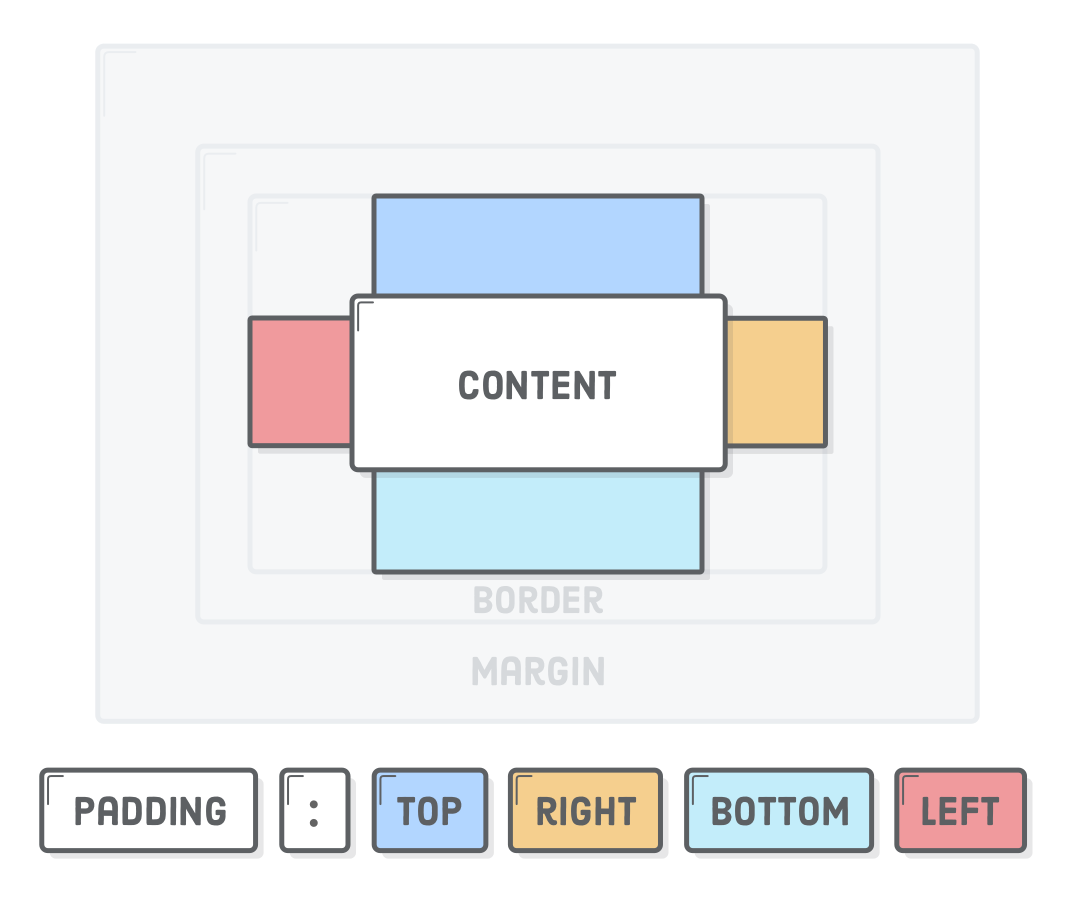

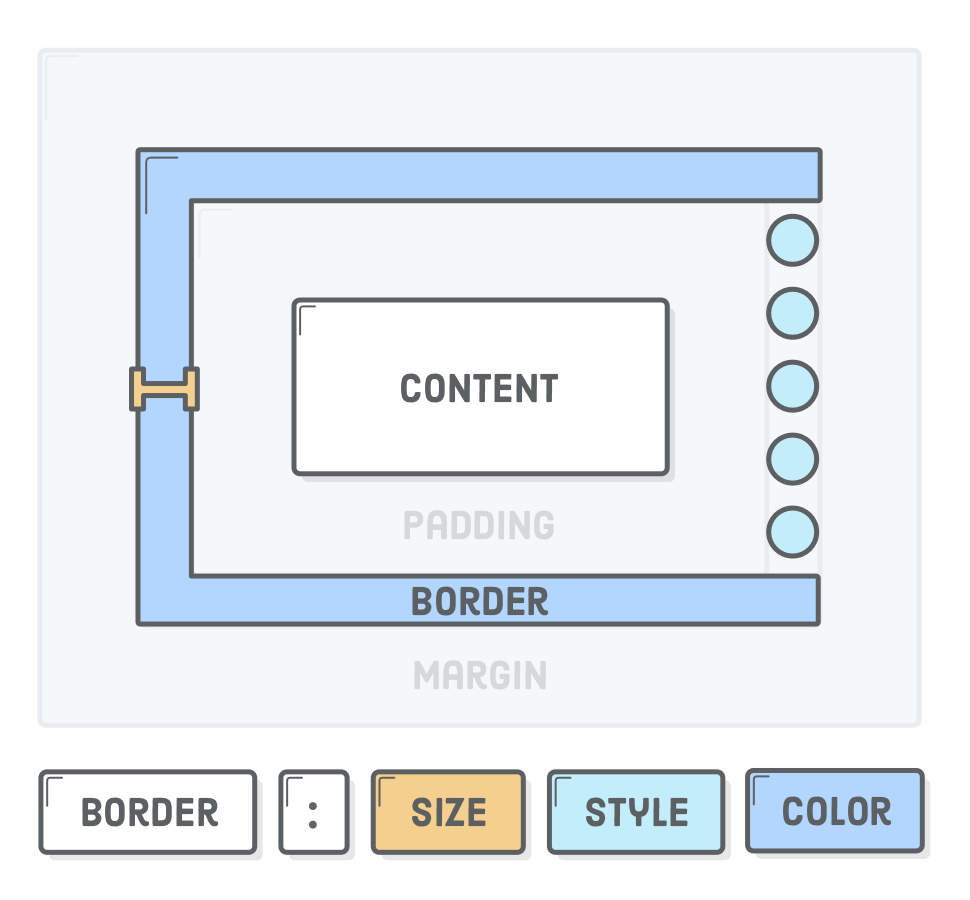

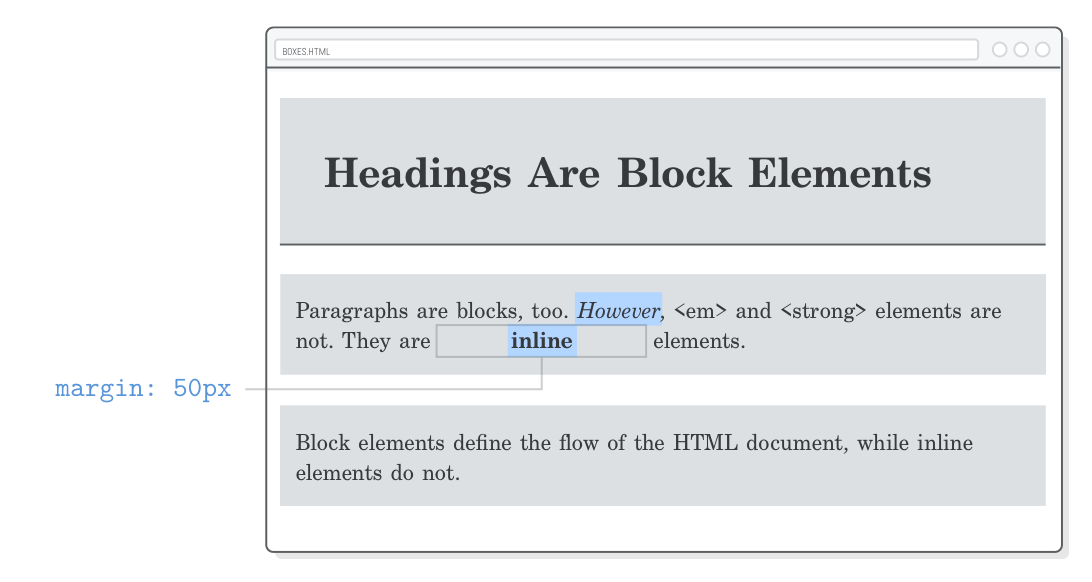

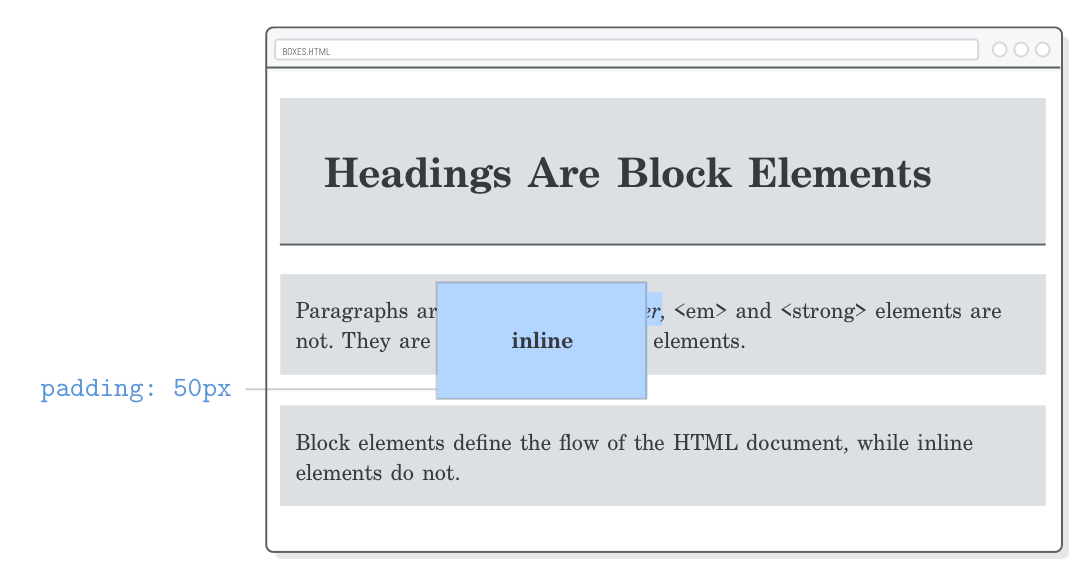

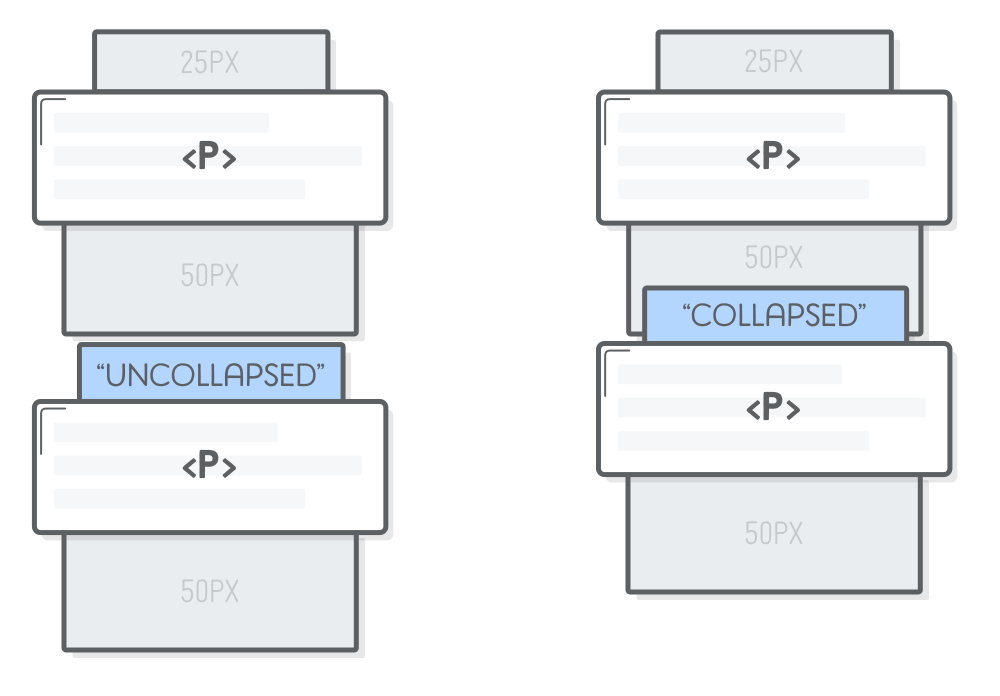

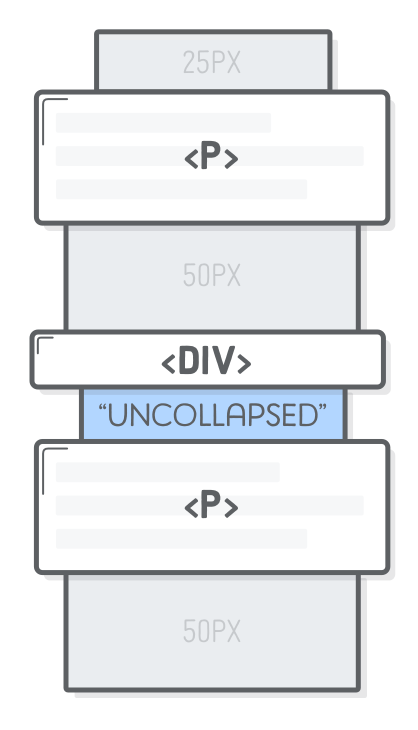

This chapter covers the core components of the CSS box model: padding, borders, margins, block boxes, and inline boxes. You can think of this as the “micro” view of CSS layouts, as it defines the individual behavior of boxes. In future chapters, we’ll learn more about how HTML structure and the CSS box model combine to form all sorts of complex page layouts.